How to explain the appearance of EVs on Pyongyang streets?

Here’s what happens every time an electric vehicle is reportedly spotted in North Korea: everybody stops and asks the same questions. How can EVs be charged in a country where the lights go out several times a day? Who drives such cars? And where could the vehicles have come from?

To understand this story, a basic question must first be addressed: Is North Korea capable of building EVs? The answer is no. The country struggles to properly manufacture even conventional automobiles. There is little possibility for EV production.

According to recent South Korean government statistics, the data point to the structural limits of the North’s industrial capacity. In 2023, North Korea produced only 350,000 tons of crude steel—just 0.5% of South Korea’s 66.68 million tons—highlighting its inability to manufacture even basic materials needed for automobile production.

The situation is even more severe in the power sector. North Korea’s gross electricity generation in 2023 reached only about 4 percent of South Korea’s, while its power generation capacity stood at roughly 6 percent. Under these conditions, investment in battery technology and the development of basic EV infrastructure, such as charging stations, appear impossible.

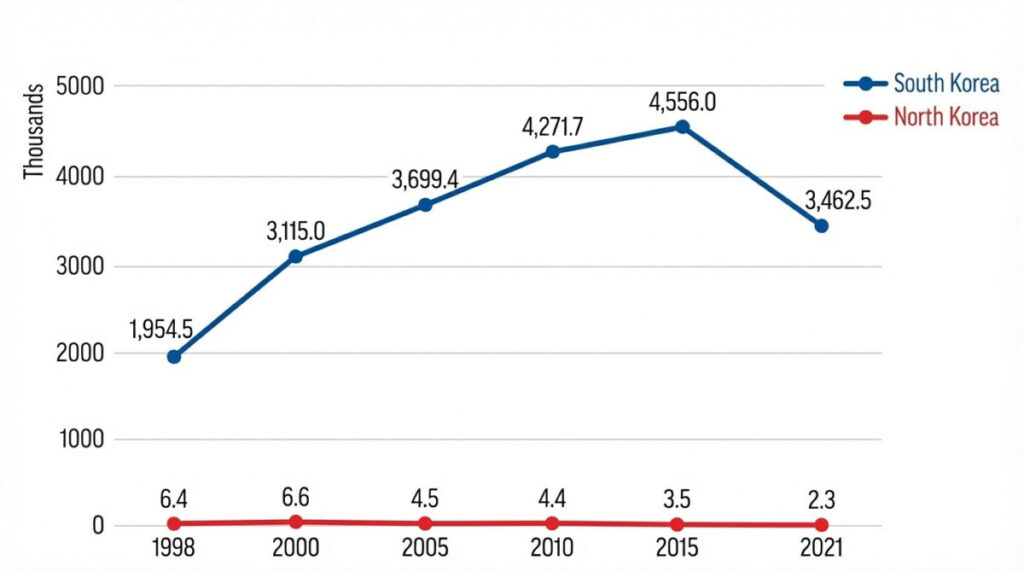

So how many vehicles does North Korea actually produce? According to the Ministry of Unification, the Sungri Motor Complex, widely regarded as the country’s largest car factory, has an annual production capacity of about 30,000 units. When thel other factories that are believed to exist in the country are included, total capacity could theoretically reach between 40,000 and 50,000 vehicles a year.

The reality, however, is starkly different. The Ministry of Data and Statistics estimates that North Korea produced only around 2,300 vehicles in 2021—the most recent year for which data are available—suggesting factory utilization rates of just 4 to 5 percent. Even then, production is known to be mostly industrial trucks and military vehicles, rather than passenger cars for civilian use.

Long-term data further underscore the decline. Since 1998, vehicle production has shown a sustained downward trend, highlighting the country’s inability to manufacture modern automobiles, making EV production even more unlikely.

If North Korea cannot manufacture EVs, where did those models seen on the streets of Pyongyang come from and how did they get there? The most likely answer is smuggling.

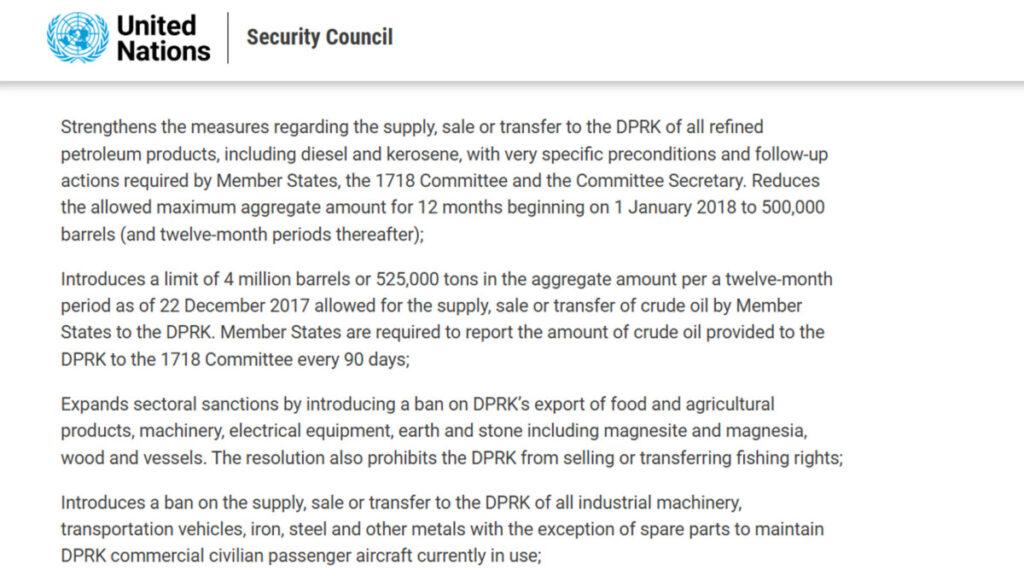

In December 2017, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2397, imposing a comprehensive ban on exports to North Korea of industrial machinery, vehicles, steel, and other metals. Despite these strict sanctions, and signs that factories are barely producing vehicles, cars continue to appear on North Korean streets. This raises questions about illicit supply routes.

China’s General Administration of Customs said bilateral trade with North Korea rose 25% to $2.73 billion in 2025, with exports in December alone increasing 21.2% from a year earlier to $257.4 million. As the details of that trade remain unclear, growing evidence suggests vehicles are being smuggled in, quietly and covertly.

According to Chinese sources, the port in Dandong, which is China’s largest city on the Korean border, is often very busy around 10 p.m. at night. Some say they heard that parts or semi-assembled vehicle units are being shipped for completion inside North Korea. Components of EVs are said to be part of these shipments. Multiple sources estimate that more than 4,000 Chinese EVs were imported into North Korea in 2024. There is also speculation that assembly plants in Rason, near the Chinese and Russian borders, are working on cooperation with Chinese companies.

If true, this trade is in violation of international sanctions.

North Korea also unveiled what it described as its own EV in June 2024, but it has drawn widespread skepticism. Chinese sources who have actually seen the vehicle said it appears to be a reassembled Chinese-made EV. Several experts noted strong similarities to the sedan named Han produced by BYD, suggesting the North Koreans have changed the logo and are calling the vehicles their own.

- How to explain the appearance of EVs on Pyongyang streets? - February 7, 2026

- 2026: In a world hungrier than ever for electricity, nuclear-armed North Korea is unable to power daily life - January 29, 2026

- Reporting the unreachable: why we need to keep paying attention - January 15, 2026