2026: In a world hungrier than ever for electricity, nuclear-armed North Korea is unable to power daily life

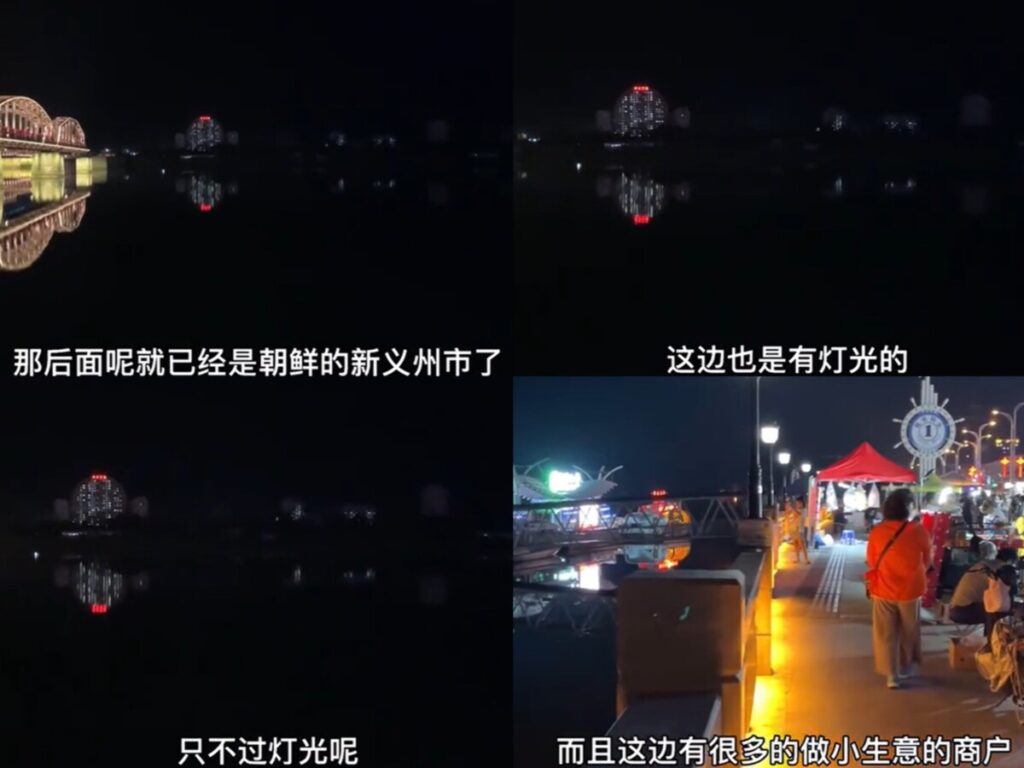

Dandong, the Chinese port of 2.4 million on the North Korean border, remains brightly lit well into the night.

At 9 p.m., neon signs glow above late-night crowds. The smell of grilled lamb fills the air. The Yalu River, the strip of water separating it from North Korea, reflects its lights like a mirror. Then the mirror breaks.

On the other side, there is nothing. “Just darkness,” as a local resident put it. “Endless darkness.”

What people across the river want most is not complicated – just electricity, enough power to carry out their daily lives. In a bitter irony, a country capable of building nuclear weapons cannot offer its people the simple mercy of light.

This year, global demand for electricity is at unprecedented levels, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Behind this surge: the global race to fuel artificial intelligence. Training and operating advanced AI models requires enormous amounts of power. Some major AI data centers consume as much electricity as tens of thousands of households.

The IEA says that demand rose by 4.3 per cent in 2024 and is expected to grow at an average annual rate of about 4 per cent through 2027. Over the next three years, worldwide consumption will increase by roughly 3,500 terawatt-hours a year. That is equivalent to adding Japan’s entire annual electricity use to the global total every 12 months.

Across the Yalu River from Dandong, a very different battle is being fought. There is no race, only scarcity. While AI reshapes humanity’s future on one side of the border, people on the other bank struggle to keep a single light bulb burning.

The numbers expose the depth of that divide. World Bank data shows that only 57.5 per cent of North Koreans had access to electricity in 2023. But the reality is worse. Access can mean as little as two hours of power a day. It is estimated that 10.96 million people, nearly half the population, live effectively outside the power grid, using little or no electricity at all.

The country’s installed generating capacity stands at 8.357 gigawatts, with annual production of about 22.4 terawatt-hours—roughly 4 per cent of South Korea’s output, according to the CIA World Factbook. Even that limited supply is undermined by inefficiencies: 18.3 per cent of all generated power is lost in transmission before it reaches users.

This is not simply a story of scarcity. It is a structural paradox. Fuel supplies have shrunk, transmission losses are extensive, power is prioritised for the military and strategic industries, and attempts to expand generation often worsen civilian hardship.

Statistics outline the crisis. But the harsh truth of it all becomes clearer on the ground.

“I’ve heard that even Pyongyang suffers constant power cuts,” someone in Dandong said. “They say that in high-rise apartment buildings there, elevators operate only during limited hours. Miss that window, and you have to take the stairs. I’ve also heard that some hospitals are forced to suspend surgeries because the electricity supply is too unstable.”

This contrasts sharply with how state propaganda portrays the capital as a “modern city.”

Along the border, markets are filled with goods. Yet the most sought-after items are neither luxury products nor advanced electronics. What people most want are small household solar power devices.

“Small solar panels are a huge help in daily life in North Korea,” the source said. “But not every family can afford these imported products. Many ordinary households have no choice but to pay a fee to borrow them.”

This is the irony of 2026. On one side of the narrow river, electricity fuels AI, data centers and revived nuclear plants. On the other, it is traded like bread.

“I’ve heard nights there feel like a return to primitive society,” the source added. “People cook with firewood or charcoal. I could hardly believe it.”

Professor Yoo Seung-Hoon of the Department of Energy Policy at Seoul National University of Science and Technology said that for countries like North Korea, where energy infrastructure dates back to the 1990s, “economic capacity” is the decisive factor in achieving modernization and universal electrification.

“For these countries, two things matter most,” Yoo explained. “They need transmission networks, and they need power plants. In some cases, power plants already exist, but there is no grid to deliver electricity to people. In other cases, it is the opposite.”

When asked how technically challenging it would be for such countries to reach a modernized level, Yoo said the hurdles are manageable.

“Building both the grid and power plants could take as little as five years if the funding is available,” he said. “In many underdeveloped countries, such projects are carried out through Official Development Assistance (ODA), and with sufficient financial support, electrification across the country and to most of the population could be achieved even faster.”

Given North Korea’s severe economic constraints and ongoing international isolation, such a scenario feels far away.

The darkness across the Yalu River reflects more than an electricity shortage. It points to the deeper forces that have left an entire country disconnected from the infrastructure of modern life.

Separated by a single river, one side surges forward, while the other continues to go nowhere.