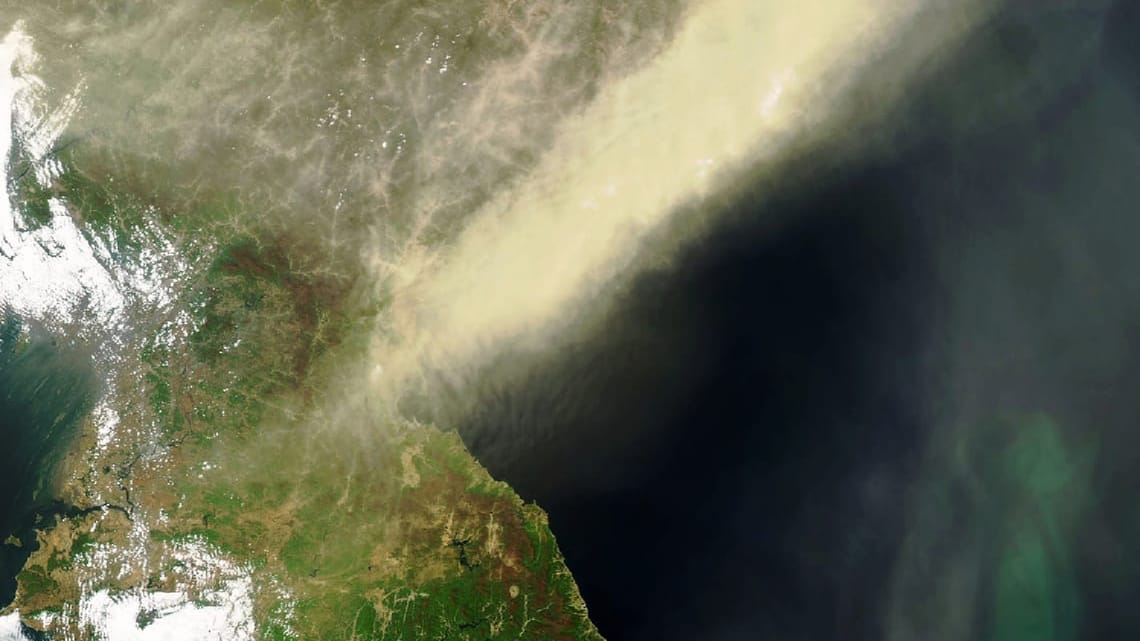

Feature: Obscured by clouds

Why does North Korea keep threatening South Korea and its allies without ever going to war? Michael Breen on theater and reality in one of the most enigmatic places on Earth.

Published with The Signal. Sign up here.

On May 21, when North Korea’s navy attempted to launch its second destroyer, the Kang Kon—with the country’s Supreme Leader, Kim Jong Un, looking on—the ceremony ended in disaster. As the ship accidentally slid off its cradle into Kyŏngsŏng Bay, the weight of the vessel crushed and ruptured parts of the hull, leaving the ship’s stern stuck underwater for two weeks.

While the failure prompted a lot of good memes and jokes, the 5,000-ton-class Kang Kon—which the navy repaired, relaunching it in June—is part of a standing, ambitious initiative to upgrade the North Korean navy’s capabilities. Just a few weeks earlier, it had launched its first destroyer, the Choe Hyon. In late April, it test-fired weapons systems, including supersonic cruise missiles. The Choe Hyon also has anti-aircraft missiles, a phased radar array, and air-defense systems—sophisticated technologies that some military analysts have concluded Russia must have helped North Korea develop.

At the Kang Kon’s relaunch in June, Pyongyang announced plans to build two more destroyers next year. In March, it unveiled a nuclear-powered submarine already under construction. In May, Kim supervised ballistic-missile tests to simulate nuclear counter-strikes against South Korean and U.S. forces. Meanwhile, Pyongyang has conducted a seemingly unending series of weapons tests.

Among all the interpretations of these military displays, one stands out: that the North Koreans are preparing a military attack. Late in 2023, Pyongyang announced it would now consider South Korea a hostile country and no longer seek reunification with it. Then, in January 2024, Robert Carlin and Siegfried Hecker—two U.S. officials who’ve worked on North Korea for decades, Carlin with the State Department and CIA, and Hecker as the former director of Los Alamos National Laboratory, the U.S. center for nuclear-weapons research—released an influential report detailing why they think Kim has made the decision ultimately to go to war.

Is this true?

Michael Breen has lived in South Korea for more than 40 years and is the author of three books on the two Koreas, including a biography of Kim’s father, Kim Jong Il. Breen says outside observers are always in the position of having to interpret North Korean weapons tests through layers of possible meaning, often difficult to parse. Still, he sees evidence for the shape of a different reality: that all these military upgrades belong to the beginnings of a transformative change—in a country long known for almost no change. After decades of privileging the military above all other institutions in North Korea, Pyongyang is now instead showing signs that it’s really focusing on economic development. Yet if he’s right, Breen says, it means Kim is trying to alter his country’s economy without altering its totalitarian politics—raising an enormous question about where and how far this change could go …

Michael Bluhm: Why all the endless public weapons testing?

Michael Breen: It’s never entirely clear what’s happening with anything in North Korea. But when it comes to weapons tests, it’s usually several things at once. Of course, one of them is a basic research need: In order to develop new weapons, you have to test new weapons. But there’s also the consideration of how a test will play at home—and another still of how it will play abroad.

Given how opaque North Korea is, weapons tests can seem to come out of nowhere. And it’s always easy for outside observers to imagine there’s a single reason for the timing—or for outside observers in the U.S., in particular, to think that reason is a message, meant for Washington—when in fact, there are often multiple reasons for the timing; and when they’re messages at all, the U.S. is just one possible audience.

Bluhm: Still, in 2024, this report from Carlin’s and Hecker’s made an influential case that the North Korean regime is gearing up for some sort of military attack. They said it’s the “most dangerous time” on the Korean peninsula since the Korean War. What do you make of that?

Breen: Well, I respect their knowledge, but I disagree with them. And to be clear, they didn’t actually say they were sure Kim was preparing for war; they were careful to say only that it looked like he was. Most analysts are somewhat mystified by what North Korea has been doing; all analysts know it’s ambiguous; and these two presented an interpretation at the pessimistic end of the spectrum.

It’s never entirely clear what’s happening with anything in North Korea.

Some context for what we’re seeing now: Toward the end of 2023, and again early in 2024, Kim Jong Un pronounced that his regime was now opposed to the reunification of North and South Korea—saying South Korea should be seen as a foreign country, like any other, as much as an enemy.

Which has enormous implications. Historically, the governments of both Koreas have considered it a sacred task—which they’ve enshrined in their constitutions—to reunify the peninsula under a single government. And in the North, that idea has been at the heart of the whole conceit for running their country like a military base.

For the most part, South Korean people haven’t taken Kim very seriously on any of this. Many just said, you know, There he goes again. But the interpretation that got the headlines was Carlin’s and Hecker’s—the interpretation that by reversing the longstanding North Korean narrative about South Koreans being our brothers and sisters suffering under the boot of the imperialist Americans, Kim created a justification for war, even a nuclear attack.

I wouldn’t see the circumstances in the country supporting that view, though.

Some more historical context: By the 1980s, it was clear that of the Koreas’ two different economic-development models, South Korea’s was the more successful—even though after the Korean War, the North had started out with the more industrialized economy. Today, there’s no economic competition between these two countries—and no one’s been expecting a military operation by either side to reunify the peninsula.

Instead, analysts have been expecting one of two things: a coup in the North to replace a leadership that badly lost its economic competition with the South; or an acceptance in the North that the South has the better model—and with that, an opening of the North’s economy, like Deng Xiaoping, then the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, opened China’s in 1979.

For a long time, it’s been hard to imagine a transformation like that happening in North Korea. But now there’s some prospect that one might tentatively be underway. When Kim Jong Il took over the country back in 1994, he realized he needed the military in order to keep himself in power, so he made it the most important element of the North Korean state. And for his nearly two decades of rule, this primacy of the military he cultivated remained in force.

Now, though, it seems the North’s decades-long commitment to that primacy is being displaced by what appears to be more of an interest in economic development and improving people’s livelihoods. We can’t know for sure yet, but if this is starting to happen—if—it could be the beginning of Kim Jong Un’s Deng Xiaoping moment.

Bluhm: What evidence would you see for that?

Breen: I don’t want to give myself to any wishful thinking, of course, but I see two big items of potential evidence.

One is the fact of Pyongyang having declared its new opposition to the idea of reunification with South Korea. It’s evidence of a major change in the country’s strategic direction, if not of the direction itself.

They know if they did anything serious, they’d be thrashed by South Korea and the U.S.

The second suggests the new direction, though: Across North Korea, we’re seeing huge construction projects—some 25 factories in all, which is about two factories for each province. It’s an enormously ambitious move intended to produce economic growth. That would sound unremarkable for most countries, but North Korea is different. The government there hasn’t had to focus on its economy at all to maintain political power. Hundreds of thousands of people died in a famine from 1994 to 1998, and the whole time, the regime never faced a threat to its control.

But that’s also a reason to be circumspect about the possibility of a transformation in North Korea: There’s still no political change. For years, Beijing tried to get North Korea to open its economy, and Pyongyang basically said, When you open a window, you let flies in. They always worried that reform or liberalization would lead to demands for freedom and democracy.

Today, it looks like they’re trying to have it both ways—to reform their economy without changing their politics. If it were another ruler doing this, I’d be more confident in saying a transformation is happening. But Kim Jong Un spent the first 10 years of his rule keeping the military happy and affirming dynastic succession.

So there’s evidence indicating the possibility of systemic change in North Korea, but there’s also the persistent question of how deep change in North Korea can ever be—and how far it can go.

Bluhm: So how would the recent defense displays fit with a potential reorientation toward economic development? That seems counterintuitive.

Breen: It does. But think of it this way: If you needed to reorient North Korea without signaling that you were surrendering anything to anyone—to keep the military happy, along the way—one way you could do that would be to puff up your posture of being a tough guy with the outside world, not least by building nuclear weapons and threatening neighbors.

Which would also explain Pyongyang’s recent diplomatic initiatives. In late April 2024, a North Korean delegation visited Iran. North Korea called 2024 “the year of friendship with China.”

In 2023, Kim had a summit with Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, and North Korea continues to supply arms and spare parts for Russia’s war effort in Ukraine. It even sent soldiers to fight on Russia’s side. Pyongyang appears to be stepping out in the world much more confidently and boldly, as it abandons the idea of reunification with the South in favor of its emerging priorities domestically and internationally.

Bluhm: About this move away from the idea of reunification: In April 2022, Stephan Haggard said here in The Signal that Kim’s missile tests didn’t ultimately disturb the stability of the Korean peninsula, because South Korea and the U.S. had established such powerful deterrents to any attack by North Korea. Do you think that’s true?

Breen: I do. The North Koreans aren’t stupid. They know if they did anything serious, they’d be thrashed by South Korea and the U.S. Over the past 20 years, Pyongyang has provoked small incidents here and there, but they’ve always been very careful not to trigger a major retaliation.

What Kim really wants from the Americans is a peace treaty to end the Korean War formally—because then he can say, Okay, so why do you still need troops in South Korea.

That said, North Korea’s nuclear capability does remain a serious threat—as does North Korea’s ability to strike the U.S. mainland with non-nuclear missiles. Pyongyang does have those capabilities.

Bluhm: Thinking about the dynamic between North Korea and the U.S.: In 2022, after Kim ended a moratorium on missile tests, Haggard said that Kim’s primary concern was his relationship with Washington. How would you say the U.S. figures in Kim’s calculations?

Breen: Historically, the North Koreans used to play the Chinese and the Russians off against one another, to see who’d give more aid. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Pyongyang quickly reached out to the U.S., apparently trying to continue its old strategy, only now with Washington replacing Moscow. But it didn’t work, because the U.S. has consistently required that North Korea give up its nuclear-weapons program—which it just isn’t going to do.

The North Koreans have also, historically and very publicly, cast the U.S. as their main enemy. Which remains very useful for Kim’s domestic position today, because it makes him look like a determined underdog standing up to the big, global bully.

Kim would also like to sideline South Korea as much as possible and get some money out of Washington—without working too closely with the U.S. What Kim really wants from the Americans is a peace treaty to end the Korean War formally—because then he can say, Okay, so why do you still need troops in South Korea.

At the same time, Pyongyang is also strengthening its relations with America’s enemies more intentionally and more clearly than before—which is creating the appearance that Kim has given up on any expectation of progress with the U.S.

Bluhm: A lot of media reports have suggested that Kim was very disappointed by his 2019 summit in Hanoi with U.S. President Donald Trump—that this was the moment when he gave up the longstanding goal of normalizing relations with Washington. Carlin and Hecker say this was when Kim decided on a new strategy of increased belligerence and confrontation with the U.S. How do you see Kim’s military moves since fitting with this picture?

Breen: I see two possibilities here. One is Carlin and Hecker’s argument that Kim has given up on normalization—at least until there’s a new administration in 2029, when there might theoretically be some reset with Washington. In which case, Kim’s objective meanwhile would be to strengthen relations with Putin and other American enemies.

The other possibility is that Kim intends increased belligerence and confrontation to push the U.S. toward normalization talks. It can seem he’s sending a message: We’re not going to give up our weapons, and we can be dangerous—so why not talk to us. Let’s look for some sort of realistic agreement we can come to.

But it’s unclear to me to what extent Kim’s behavior is directed toward the U.S. at all. People in Washington tend to think everything revolves around America. And a lot can. I’m just not entirely sure that’s the case here.

Though the nuclear threat is real, any U.S. administration focusing mainly on nuclear weapons isn’t going to make any progress with North Korea, anyway, because the North Koreans simply aren’t giving up their nukes.

The Americans and their allies have no real vision for North Korea or Northeast Asia; they only care about nuclear weapons here. But there’s tremendous potential in Northeast Asia for a broad regional strengthening of democracy, human rights, the rule of law, and free markets; South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan are already far down that path. Washington could be helping with those considerations generally and these countries specifically when there’s an opportunity. Instead, it’s focused on nuclear security narrowly. Their position on North Korea is just, If you don’t give up your nuclear weapons, we aren’t even talking to you.

And though the nuclear threat is real, any U.S. administration focusing mainly on nuclear weapons isn’t going to make any progress with North Korea, anyway, because the North Koreans simply aren’t giving up their nukes.

Bluhm: You mention that North Korean officials traveled to Iran in 2024, and that Pyongyang has worked more closely with Russia since it invaded Ukraine. How do Pyongyang’s foreign alliances look today?

Breen: It’s interesting, North Korea almost entirely shut down after the pandemic broke out. Partly because Kim himself got Covid, the entire system became very serious about it. They didn’t even allow diplomats to re-enter the country.

But things have since reverted more to normal. Before the pandemic, in 2019, North Korea sent a delegation to Iran, so we shouldn’t read too much into the 2024 trip. Western scrutiny of Pyongyang’s relationships with Russia and Iran is intense because of the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. And true to form, Kim is picking the sides opposed to the U.S.

Still, I see a new confidence in North Korea that comes with saying, We’re not interested in reunification anymore; South Korea is just another country that we still have problems with on our border. We’re firming up ties with countries that treat us with respect and help us get around unjust sanctions. So if the sanctions ended, Pyongyang’s relations with Moscow and Tehran might not be as important.

Bluhm: At the same time, relations with China seem to have cooled—though maybe that too is hard to say entirely, with both countries being so opaque. How do you see the relationship between Pyongyang and Beijing these days?

Breen: They’re close formally but not so close in reality. China’s ties with North Korea were forged back in the 1950s, during the Korean War, when the People’s Republic rescued the North from defeat. Many Chinese soldiers died for this.

Today, many Chinese admire South Korea for its culture and its economy—and China’s economic relationship with South Korea is far more important than with North Korea. Beijing and Seoul do an enormous amount of trade together.

Meanwhile, there are a significant number of ethnic Koreans living in China near the border with North Korea—and they tend to be very glad they’re not in North Korea. They’re freer and wealthier in China than they would be there.

That said, ties between Beijing and Pyongyang are warming—but the context there could be that Kim is trying to revive the old competition between his two major allies, the Russians and the Chinese. It can seem he’s trying to play them off each other. As far as we can see.

- Feature: Obscured by clouds - October 29, 2025