Feature: The way of Kim Jong Un

How is political upheaval in South Korea affecting North Korea? Soo Kim on what’s driving Pyongyang’s increasing hostility toward Seoul.

Published with The Signal. Sign up here.

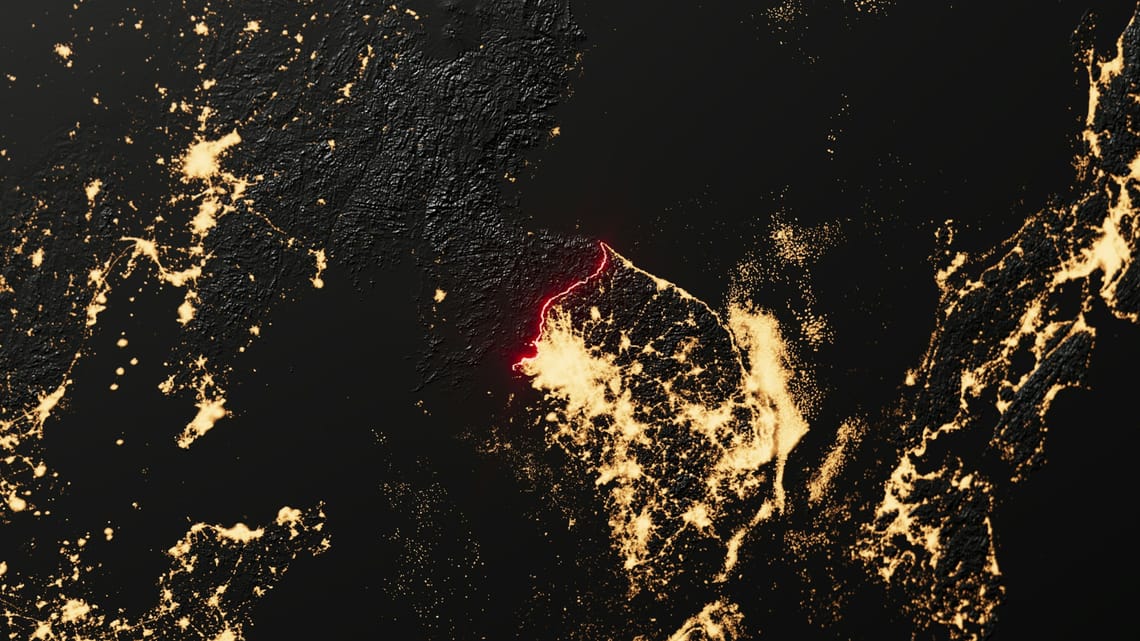

In late 2023, North Korea’s Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un declared he no longer wanted to reunify with South Korea. Seoul was now Pyongyang’s “principal enemy.” Since then, Kim has tested new and more powerful missiles, launched his navy’s first destroyers, and unveiled a nuclear-powered submarine under construction.

Kim made this shift when South Korea was ruled by President Yoon Suk Yeol, a conservative who took a hard line against the North. But then on December 4, 2024, Yoon made a power grab: He declared martial law, disbanded the legislature, and said some members of the liberal opposition—the Democratic Party of Korea—were working with North Korea to undermine the South’s security.

Yoon’s gambit failed. Members of the National Assembly—including some from his own party—sneaked past soldiers that same night to meet in the chamber and revoke his declaration. Yoon eventually backed down, the legislature impeached him, and the Constitutional Court removed him from office in April. He’s now awaiting trial on charges of insurrection and abuse of power. On June 3, voters chose Lee Jae Myung of the DPK to replace him.

Lee has made conciliatory moves toward Kim—a major change from Yoon. He pledged to reopen communication channels with Pyongyang, suspended propaganda broadcasts into the North, and in August, the country dismantled some loudspeakers along the border.

How is North Korea responding?

Soo Kim is a former analyst at the Central Intelligence Agency and the RAND Corporation, where she tracked East Asia and the Korean Peninsula. Kim says that despite predictably bombastic rhetoric from Pyongyang about events in Seoul—and despite how hard it always is to know what’s really going on inside the North Korean regime—one thing seems clear: Kim Jong Un has no interest in engagement with South Korea.

The supreme leader is playing a long game, Kim says, and his primary interest is the survival of his family dynasty—not dissolving it in reunification. He sees nuclear weapons as his best tool for strengthening the regime, and his growing partnership with Russia is valuable too. He sees little to gain through diplomacy with the South—and meanwhile, the idea of reunifying the Korean Peninsula recedes further with each new generation in both Koreas.

Oliver Mills: In late 2023, Kim Jong Un said he no longer wanted reunification with the South and saw it as an adversary like any other. What do we know about why he did that?

Soo Kim: It’s related to the degeneration of Korean relations and the development of North Korea’s nuclear weapons.

Back in 2017—when Moon Jae-in was South Korea’s president and Donald Trump was in his first term—Seoul tried to frame itself as a mediator of inter-Korean relations. Pyongyang rejected that. It didn’t want the South meddling in its dealings with the U.S. and saw Moon as a hindrance. Then, when Moon lost the election in 2022, Pyongyang no longer saw any utility in engaging with the South, because Moon’s successor, Yoon Suk Yeol, refused to make concessions to North Korea.

Both Koreas used to talk about reunification like it was a realistic outcome, but it’s not easy for either side; that’s why they’ve been separated so long. Kim is realistic about that. Now he’s got nuclear capabilities, and he’s cooperating with Russia on the war in Ukraine, so it seems he thinks he doesn’t need to engage with South Korea anymore.

South Korea’s current administration, led by Lee Jae Myung, has expressed unconditional patience toward the North and is taking independent steps toward reconciliation. However, as Kim Jong Un’s sister Kim Yo Jong recently stated, North Korea no longer has an appetite for reunification. They want to go it alone—on nuclear talks, on all relations with Washington.

There’s really no place for South Korea right now in engagement—much less reunification. Pyongyang has shut the door, calling out South Korean cabinet members to tell Seoul it doesn’t want to deal with it and doesn’t see it as a partner. Instead, it sees the administration in Seoul as an obstacle to its nuclear ambitions and any potential opening for a deal with Trump.

North Korea no longer has an appetite for reunification. They want to go it alone—on nuclear talks, on all relations with Washington.

Mills: So relations between the North and South had been poor for some time, and Kim has had nuclear weapons for many years. What do we know about why he decided to make this major strategic shift when he did?

Kim: It relates to how the outside world views North Korea’s weapons. Pyongyang’s short, intermediate, and long-range ballistic missiles are increasingly seen as a normal part of the world’s security dynamic, so we’re no longer fazed when Kim Jong Un tests a missile.

Kim has capitalized on this. Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons are a credible threat, but the U.S. still hasn’t recognized North Korea as a nuclear state—partly because there’s no real way for Washington to deal with that. It’s a unique situation.

Kim’s very attuned to that. If unification isn’t possible, and he already has nuclear weapons—then severing official ties makes an even stronger case for retaining his nukes. Designating South Korea as its principal enemy allows Pyongyang to say, We have an enemy, so we’re going to strengthen our capabilities—and there’s no way for the world to convince us to get rid of them.

Mills: How do you see Kim’s shift in the context of the two countries’ relations since the end of the Korean War?

Kim: Simply put, times have changed.

North Korea’s system remains similar—no change in the Kim dynasty, and the population is still restricted in movement and freedom of speech. The X factor here is the North’s nuclear weapons.

During Kim Il Sung’s rule, from 1948 to 1994, the goal was to reunify the two Koreas under the North’s ideology; that made sense at the time, as not much time had passed since the split. In Kim Jong Il’s era, reunification was still in the picture, but Pyongyang leveraged this willingness to sell “engagement”—economic cooperation and cultural exchange—to get money.

Over time, the growing rift between the two Koreas—economically, socially, politically—has made it ideologically unrealistic to unite them.

Now we have Kim Jong Un, who’s shown himself over the years to be much more ruthless than his father or grandfather. We’ve also seen greater steps toward nuclear sophistication in his less than two decades of rule, which—combined with this rupture on unification, and changes to Pyongyang’s constitution—says a lot about where his mindset is.

Mills: Was reunification always a high priority for Kim’s father and grandfather, or did that wax and wane?

Kim: Under Kim Il Sung, it was definitely a priority, after the trauma of the war. But with each new generation, the idea of reunification became more and more diluted, even though it was written into the constitution as a goal.

Both countries were facing the realities of how each had evolved. South Korea became more westernized and reaped the benefits of integrating with the international system, while North Korea became much more isolated. The directions the two countries took only made reunification more difficult.

Pyongyang described the declaration as a sort of crazy attempt by South Korean leadership to seize control—which is pretty ironic, given North Korean standards.

Kim Jong Un has taken a tougher, more recalcitrant stance on reunification, largely due to his expansive weapons system. Kim clearly understands that reunification has been diluted as an idea, and he wants to capitalize on the nuclear progress he’s made over the years.

Crises elsewhere—wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, U.S.-China tensions—have distracted from North Korea’s nuclear capabilities being a primary concern. Unification is now a pipe dream for both sides, and Kim is smart enough to realize that even though it’s been removed from the constitution as a goal, the two countries still won’t go to war any time soon.

Some people on the peninsula have concerns about the future direction of the U.S.-South Korea alliance, so the stars have aligned for Kim to maintain his grip on these weapons without having to deal with the consequences of having them. With so much going on in the world right now, it’s hard to pay much attention to the threat from North Korea.

Mills: How did North Korea react to Yoon’s declaration of martial law in December 2024?

Kim: Surprisingly, North Korea didn’t respond immediately. Instead, Pyongyang waited a week to say something; they wanted to see how things would play out, and recognized there was a risk of backlash to an immediate reaction.

When they did respond, they tried to craft a narrative in favor of the North’s political system and leadership. Some people might have expected a quick response, but criticizing a country already designated as their principal enemy might have had an adverse effect, drawing too much attention to North Korea’s own political system and Kim Jong Un’s leadership.

Eventually, Pyongyang moved to widen the divide between the two Koreas, by criticizing the South’s regime and calling it weak compared to the North.

It stirred up ideas that South Korea is a tightly controlled society, and used Yoon’s declaration to frame Seoul as a fascist regime—labeling the move as an attempt to tighten his grip over the South’s population.

Mills: When Yoon declared martial law, he accused members of the opposition Democratic Party of Korea of working with Pyongyang. Did the North react to these charges?

Kim: No. Interestingly, Pyongyang described the declaration as a sort of crazy attempt by South Korean leadership to seize control—which is pretty ironic, given North Korean standards.

This was similar to Pyongyang’s reaction to the South Korean military coup in 1980, when General Chun Doo-hwan seized power after President Park Chung-hee’s assassination and then expanded martial law to consolidate power. Pyongyang used that episode as an opportunity for propaganda comparing the two systems; it framed North Korea as superior, demonstrating to its own population that the South had political dysfunction that didn’t exist in its system.

Mills: How did Pyongyang react when Yoon was impeached within two weeks?

Kim: North Korea kept this reaction pretty mum and issued a report pointing to weaknesses in South Korea’s institutions—calling it a fascist dictatorship. The reaction was all rhetoric—no show of military force, no weapons testing, just a cynical readout of Seoul’s political system.

We’re apt to see a lot of South Korean pining toward North Korea—and North Korea rebuffing the South.

People may have expected more from North Korea at the time, but Kim Jong Un knew that a stronger reaction risked backlash toward his own leadership and political system. He was also cognizant that, having already pushed reunification out of the picture, the optics of reporting on a leadership crisis in a country already labeled as its principal enemy might look odd for North Korea.

Mills: After Yoon’s impeachment, Lee Jae Myung won a special election for the presidency in June. He’s taken a much friendlier tone toward the North. How is Kim reacting to Lee’s conciliatory moves?

Kim: Last week, Kim Yo Jong issued a statement calling Lee unfit to be North Korea’s partner.

She called out top cabinet ministers too, to make sure Seoul knows that North Korea has no desire whatsoever to engage with the South right now; she made clear the North looks with disdain on whatever peaceful gestures the Lee administration is trying to make.

Lee has talked about unilaterally reviving the 2018 inter-Korean military agreement—which North Korea suspended in December 2023—and taking independent steps to ensure peace can be achieved without fighting. But that’s all been rebuffed by Pyongyang.

Lee clearly gets it. He knows that what he’s saying isn’t being received favorably by the North—but from his perspective, he can at least demonstrate to Pyongyang that Seoul harbors no threatening intentions.

Lee also knows this won’t be taken as sincere, but these gestures are basically the best he can do right now, given his situation and North Korea’s lack of receptivity. In the next few months, we’re apt to see a lot of South Korean pining toward North Korea—and North Korea rebuffing the South.

Mills: Earlier this month, South Korea said Pyongyang had started to dismantle its propaganda loudspeakers near the border in response to Lee’s move to suspend broadcasts and dismantle the South’s speakers. Pyongyang’s response was that this unequivocally did not happen. What’s going on here?

Kim: That incident was pretty comical. Seoul was saying, We’re going to dismantle our loudspeakers—and look, North Korea did too. Not long after, North Korea said, No, we didn’t.

This shows the current discord between North and South Korea. It shows just how much animosity Pyongyang has for the South—animosity, or indifference. It can be hard to tell the difference. Either way, it was a bold gesture by Seoul—but one the North Korean administration seems just to have ignored.

Mills: Has the turmoil in the South since the declaration of martial law affected North Korea’s strategic posture toward the South?

Kim: In the big picture, I don’t think it has.

You have to remember, North Korea is playing a long game. We see changes with elections in countries like the U.S. and South Korea, where strategy can change every four or five years under a new leader—but meanwhile, North Korea is just staying the course. Until the day Kim Jong Un dies or gets overthrown, their path will probably stay the same.

What Kim says about the declaration of martial law failing might be interesting—but all his talk about the superiority of North Korea’s system is a survival strategy. Shifts in South Korea’s democracy are interesting, but they don’t change the calculus around Pyongyang’s continuing build-up of nuclear weapons. Kim’s made it very clear he’s going to keep ramping up their weapons research and construction.

- Feature: The way of Kim Jong Un - October 29, 2025